It is possible to apply for a higher user level (follow the REGISTER button) and thus be able to add to or edit certain records in the system, depending on the level given.

On-line databases |

| Once it was possible to do research and format then display material on a web page, but as the available sources of information grew and morphed it became much more practical to use spreadsheets which could then be indexed and presented as lists. That was fine until it became necessary to define relationships and adjust indices (order of listing) and things became more complicated. With the development of PHP it became possible to maintain everything on line which is what has been done in Myrasplace. This becomes very convenient because the actual data files can stay on the server and it is only the manipulation of them that changes. This brings a new set of challenges because care is then necessary to present all information according to a common style and rationale. This is particularly true of ships and passengers where actual names may be duplicated. Ship owners had a nasty habit of replacing their vessels with another ship of the same name and soon we all have problems.Parents do the very same thing and carry a common name down the generations. Oh waily waily waily! How to get around that! Fortunately PHP coding provides a number of options to overcome this and this diatribe is intended to provide a way to optimise the use of the data, with common subjects listed to the left in the style of a FAQ file. The links take the reader directly to headings below...

|

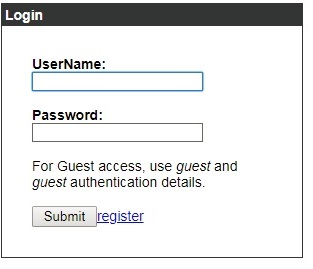

| The default user name is GUEST and the password for that is also guest. It is possible to apply for a higher user level (follow the REGISTER button) and thus be able to add to or edit certain records in the system, depending on the level given. |

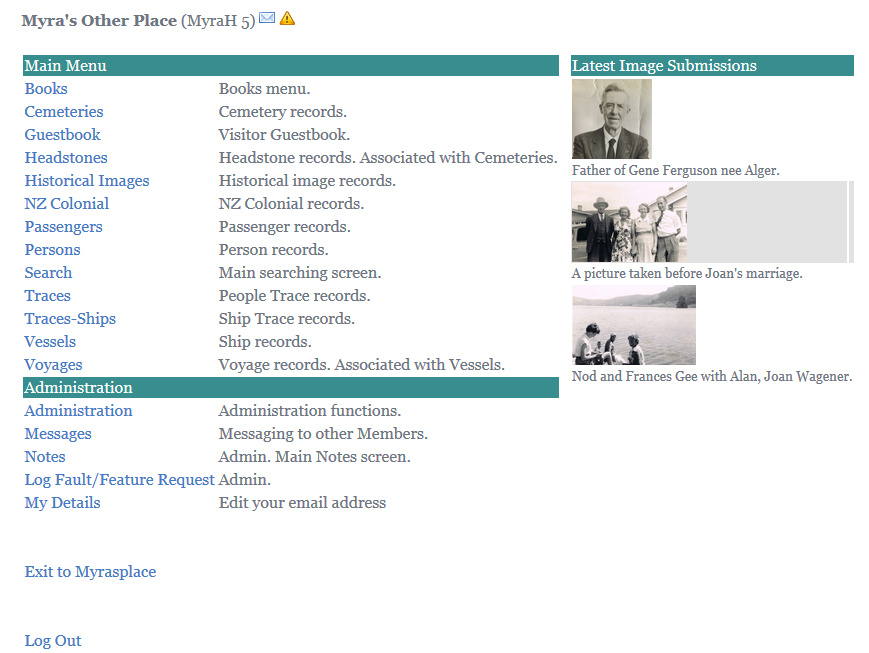

ARRIVAL SCREEN |

|

| This is the User screen everyone arrives at, depending on their access level. Note that there are additional menu items relating to features in beta format (still under development) as well as utility screens for the system overall. |

| The menu choices are for the most self-explanatory but it may be useful to know that the General Search option is a Meta search that looks at the entire table structure for nominated terms and reports which sections they mat be found in. Other menu options generally pertain to the chosen subject, It should be noted that with any ship related search (vessel, voyage, passenger) where there is a possibility of having more than one vessel sharing a name, then it is wise to look under vessels first and determine which variant is most likely. MOP4 (above) also shows pictures from the historical images records, displaying any recently provided pictures from users. That feature is in Beta and will be refined over coming weeks. |

VESSELS SEARCH

| Searching for Bombay alone will in this case give a single result and miss the other two vessels on the register... Entering the same vessel name ('Bombay') with the LIKE option will bring up all three vessels. |

VOYAGE SEARCH SCREEN

| This is what comes up with a click on Voyages. The right side of the entry screen is where the target name is typed in while the centre part (shown expanded) is where various more complex iterations may be applied. Normally the target ship name is entered. If however there may be variants of the ship name, as described earlier for Bombay, it becomes possible to add the choice on the left box to show LIKEwhich means the results will include the variants. Thus entering Bombay with a LIKE option will cause ALL the variations to show. |

VOYAGE-PASSENGER PROTOCOLS

Much of the material in the databases comes from newspaper reports of the day for which the printed detail may be (to say the least) inaccurate, especially in regard to names and to navigation details printed as 'Captain's report'. Similarly passenger lists on line tend to incorporate that first error. This is one of the reasons the MOP database includes references to genealogy files where a lot of data can be recorded beyond the simple passenger name.

By working backwards from NZBDM files and Obituary records it is possible to determine the age of a passenger at arrival. This in turn allows identifying the relative members of a given family, expanding from 'Mr & Mrs Smith plus 4 children' to a defined list of names and ages.

Those genealogy files are NOT intended as final family histories but are used as collections of threads. They are made available on request and a version of each (in GEDcom form) is in the dowloads section.

VOYAGE SECTORS

Anybody researching voyages and passengers thereon soon realises there can be a problem with a multi-leg voyage. MOP records each known leg in the VOYAGES part, but it then becomes a problem to determine where people got on and where they got off. This is true for voyages that came from England that went to a number of ports (e.g. Gravesend-Sydney-Auckland-Napier) as well as the steamer-sailers that ran from Melbourne to (say) Bluff-Dunedin-Lyttelton-Wellington and return In this latter case passengers are picked up and dropped off with a minimum of formal recording which gives problems.

Since MOP records each known sector (and sometimes adds more later as they become known) a researcher must be very careful with the passenger names. Usually a name will be showing an embarkation date and port, plus an arrivals date and port. This may bridge several intermediate sectors. Thus a passenger getting on at Gravesend and travelling to Nelson in New Zealand, then to Wellington, then Dunedin where he/she is recorded as arriving, will assume that they have been on that same ship on all the included sectors.

| TYPES OF SHIPS |

When we make lists of ships we need to define a ship type as well as a name. Sometimes the type is critical in defining a particular vessel. Here are a few of these, with notations. I am acutely aware that my natical expertise is limited so please, if there are people out there who smile at my terms and explanations, please feel free to email Alan or Myra. Ship This refers to a 'Fully Rigged Ship' and is what is meant when a newspaper record says 'Ship', as in 'Mandarin; Ship, 600t', with the 600t referring to tonnage (pre-metric, so 'tons' not 'tonnes'). A ship like this will usually have 3 masts and all three will have square sails as well as a few narrow triangular sails. Each mast is actually in two main parts; the lower section is firmly attached to the keel structure of the ship while the upper part is joined at the point called (illogically) the 'Top'. The various vertical ropes tie both back to the bulwarks - the hard rail running down both sides of the ship. Barque A Barque is very similar to a Ship but does not have a full complement of squaresails. Instead it has one mast dedicated to what we modern people call 'normal' sails and the purpose is to provide more manoeverability at the cost of power. Both types of ships can be called 'clippers' which was a term derived for a dedicated style of vessel such as the East Indiamen' or 'Tea Clippers'. Often a Ship will undergo refit and be converted to a barque as less crew are required and as usual it comes back to money... Schooner Generally a schooner has two masts with one higher than the other, the different style being referred to as a 'ketch rig' versus a 'schooner rig', but sometimes a schooner will also carry squaresails at the very top of her mast, creating a sub-type called a 'topsail schooner'.. This gives her speed while the other sails retain her mobility. The tradeoff is manpower as topsails require more crew to manage... In the tropics or in the Mediterranean, ships with squaresails are less popular because they sail best with a steady wind going in the one direction. As soon as it's necessary to tack, that is to sail against or at an acute angle to the wind, squaresails become much less useful. In the tropics winds can come from any direction and a vessel has to be able to respond and thread her way between reefs and islands. This is no place for a square-rigger for local currents can take her to destruction without a breath of wind. In addition, close to the tropics is where the cyclonic storms are generated and these to are not good for ships relying on squaresails. Steamers Here we have to speak of the differences between steam and sail in a historical context. Large sailing ships have always had a problem getting off the starting blocks; that is, getting under weigh. This is why a fleet in preparation is anchored offshore where ships have enough sea room to get clear of their anchorage. This is not always true; some harbours are ideally placed to allow vessels to get out of port, but the vast majority do not have that convenient luxury. For this reason the development of the steam engine as related to ships was a godsend to mariners because they could at last conveniently tow their big ships out to where they could catch the wind. If you read the earlier bit about how a sailing ship got away you will realise the phrase 'catch the wind' is a simplification. Nevertheless most cities and harbours were located on the mouths of rivers and it was a problem to get your large ship away to sea. This was true even for the first immigrant ships and in London and Glasgow and Liverpool steam tugs were very quickly developed. At that time steam inferred a wood-fired or coal-fired boiler and someone dedicated to heaving or shovelling fuel into the fire. For those ships going to far places with no facilities special care had to be taken to anchor their vessels in a place where wind and tide would do the job, at least until someone imported a steam vessel and started chopping the trees down. Dunedin in New Zealand is a good example of this for the entrance to the Otago harbour is narrow and the prevailing wind tends to come straight down the harbour into the faces of the new arrivals. Getting a steam vessel in Port Chalmers was one of the highest priorities and once they had one they developed a protocol wherein the arriving ships anchored offshore or simply sailed back and forth until signalled to approach. Of course steam was much more useful and began to be used as the primary motive power of non-sailing ships and once humans learned to build vessels of iron (later steel) the sky was the limit, that is as long as you had coal to hand. Smart engineers soon solved the problems associated with both sailing (no wind!) and steam vessels (no coal!) by building hybrids. These consisted of one or more steam boilers in a vessel that retained its sails and which could easily get away from a wharf and then put the sails up and sail to some distant place where they could fire up the boilers once again and make landfall. Steamer-sailers These hybrids were very popular in Australia and New zealand because they could transport a lot of material and lots of people. They made money! Both countries relied heavily on coastal transport which soon caused a great number of similar vessels to be built and put into service. It should be noted that the MOP records define a steamer-sailer with an addition to the name. Thus Aldinga s.s.s. was a steamer sailer, while Comet p.s.s. was a steamer-sailer paddleship; it could use paddlewheels AND proceed under sail. Incredibly these types of ships sailed between Australia and New Zealand!. As the age of sail faded and large screw steamers (as opposed to paddle steamers) could operate over longer routes, these hybrid vessels were not replaced and today we have large ships with the designation SS as oposed to s.s.s. (steamer sailer) or s.s., the harbour-bound little steamer that towed other boats everywhere... Coal supplies If you had any kind of steam vessel you had to boil the water with a fire. Initially this might be lengths of timber stacked alongside the boiler, but trees do not grow as quickly as boilers burn wood, so in a fairly short time you were out of wood. It is fascinating to record the purposes of the small vessels serving Auckland for as white settlement occured there was a need to burn wood in houshold and industrial fires. Very soon there were no more trees so dedicated small ships went up the coast and out to the islands and took away the trees from there as well. This couldn't last, and once a source of coal was found those same vessels began to transport it to the city. This did not solve the problem for the growing number of steam vessels, so a thriving business grew up in transporting coal from Newcastle in Australia's NSW province across to every substantial port in New zealand as well as up and down the coast of Australia itself. While coal was found in many places in both countries, there was very little in the way of roads to get the stuff from mine to user. Except ships. |